Born in Munich, Germany, (1947) Dr. Lee Spence is an internationally known expert on shipwrecks and sunken treasures. He received one of the first five doctorates (Doctor of Marine Histories, College of Marine Arts, 1972) ever awarded anywhere in the world for marine archaeology and he has long been considered one of the founding fathers of underwater archaeology. He has published more than two dozen books on shipwrecks, served as an editor for a number of magazines about diving and treasure and carto graphed and published maps about shipwrecks and archaeology.

He is the owner and creator of the web portal Shipwrecks.com and one of the founders and owners of the International Diving Institute, a school for professional divers. He is also president of the Sea Research Society with over 20,000 members. Lee was so kind to answer my questions by mail and I really hope that I will have a chance to meet him in person one day.

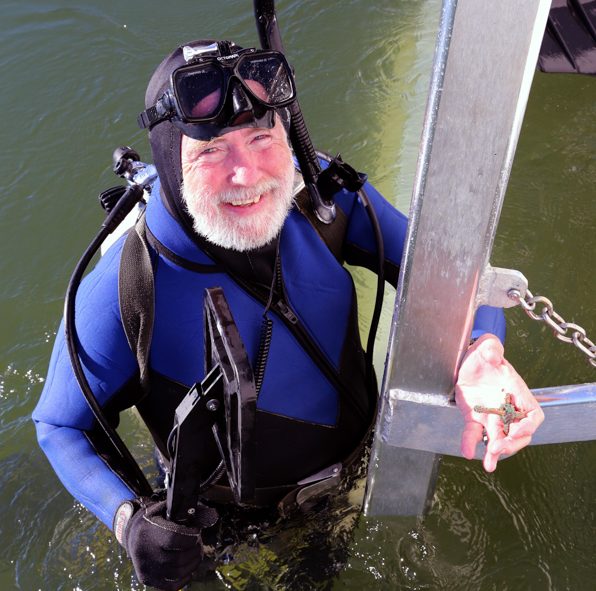

On the ladder of the RV Sea Reaper with a small metal detector produced by the German company Secon.

Tell us a bit about yourself. You were born in Germany and moved to the U.S. as an infant. What type of person are you? What motivated you to explore the underwater world? How did your career develop?

First and foremost I am a person who believes in my own dreams and I am willing to spend the time and do the hard work to make my dreams come true. Because I have confidence in my abilities, I am more or less fearless and don’t give up easily, which helps as shipwreck search and salvage is one of the most dangerous and difficult professions in the world.

As a child I read books like Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson, Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe, and The Silent World by Jacques Cousteau. I also read about the world’s great explorers and archaeologists. They captured my imagination, expanded my dreams, and I wanted to have similar adventures, find artifacts and treasure and make important discoveries. The sea seemed the last largely unexplored place in the world, so I focused all my efforts on it. I was fortunate to be one of the first to see shipwrecks as archaeological sites and, when I was 13 years old started writing to and sharing my finds with people like Mendel Peterson, head of underwater exploration at the Smithsonian; Edwin Bearrs, Senior Historian at the United States National Parks service; and Luis Marden at the National Geographic Society, each of whom were making their own shipwreck discoveries. They had no idea how young I was and, because I was helping them answer their own questions, and was making new discoveries, they quickly thought of me as a colleague. I was helping them so they helped me. By the time we actually met, I had made discoveries equal to or greater than their own, so my age no longer mattered. My 1965 discovery of five wrecked blockade runners from the American Civil War was written up in the New York Times, and major newspapers and magazines around the world. Collectively those steamers had carried thousands of tons of cargo, and we raised over a million individual artifacts. All of those things together launched my career.

I read that you built your first diving gear by yourself at the age of 12. What material did you use and how did that dive go? What did your parents say?

I used a military style, 5-gallon gasoline can filled with an air bladder that I had made by cutting up and gluing together tubes from car tires. I cut holes in the gas can so the water pressure could squeeze the air. I added straps and weights so I could wear it on my back. It had a tube running to my mouth with a small valve that I held between my teeth. I had to press a small lever with my tongue to let in each breath of air. The first time I used it, water came in with the air and I almost drowned. It only allowed me to stay down a short time, and I achieved that in part by skipping breaths. It was several more years before I was able to save up enough money to buy a second hand, double hose, scuba regulator and tank.

What did you feel when you went under the surface for the first time?

I felt like I was starting the greatest adventure on earth. Now over a half-century later, I am still on that adventure.

What motivates you look for wrecks?

For me its never been about money, it has been my love of history. But it has also been the thrill of discovery and the desire to be remembered for those discoveries.

Which was the first wreck that you discovered?

The very first wreck I found was a riverboat in the Chattahoochee River near Columbus, Georgia. Right after that we moved to France where I found several more wrecks, two were just old canal boats, but one was a ship from the time of Napoleon and I recovered handfuls of coins as well as several religious medallions. Later the same year, while we were vacationing near Barcelona, I dove on a wreck and recovered pieces of pottery that I was told dated from the Roman age. I was 12 years old.

You say that research is the key to successful and quick location of a wreck. What type of literature are you reading in order to find a wreck?

Shipwrecks were the airplane disasters of the age of sail and they were widely reported in the newspapers. I read every word carefully, noting not only the reported location and cargo, but the names of any rescue vessels and salvage efforts. Since those vessels weren’t sunk, sometimes their logs still exist and provide far more detailed inform about the wreck than the newspaper articles. Other excellent sources of information are insurance and court records.

Which are the steps of finding a wreck?

There have been literally millions of shipwrecks so there are plenty still out there to find. The first thing that I do is select an area that I have access to and then research what ships were lost in there. Then I try to decide which would be the most interesting ones to find. Of those, I try to focus on those I believe will be the easiest to locate and identify and that is usually a function of how precise the information is on the wreck’s location and cargo. Next I talk to local divers and fishermen. I also look on the nautical charts of the area to see if they might hold a clue, such as a reef with the same name as the wreck. I once had a trawl boat captain tell me about losing his nets at a spot that he and his friends referred to as the “Westward Hang.” He also mentioned another site they called the “Eastward Hang.” My question to him, was what was the one westward of and the other eastward of, as their names didn’t seem to match their respective positions. Through research I determined that they were actually the schooners Westward and Eastward, which had been lost in a hurricane over a hundred years ago. The point that I am trying to make, is try not to overlook any clues.

How many wrecks have you discovered so far?

I don’t know the exact number but it is certainly in the hundreds. I once came across the stone ballast piles of 28 wrecked ships in just a few hours time. They were scattered along the deepwater side of a small, uninhabited rocky island in the Bahamas. I later determined that of those wrecks only 4 or 5 had been found before.

Can you describe what you feel when you dive down and you see a wreck for the first time?

Its like scoring winning goal in a championship game. It’s a wonderful feeling of accomplishment.

What can you conclude from a wreck regarding the time it was in service? Which historical information can you retrieve?

Despite what many government officials would like to have everyone believe, often there is little of archaeological or historical value to be found on a wreck. But there are times when a vessel’s type and manner of construction and/or cargo can solve lingering questions, mysteries and doubts historians have had about the loss of an important vessel. The wreck of Civil War submarine Hunley, which I discovered in 1970, is an excellent example. She had not only been historically important in that she was the first submarine to actually sink an enemy ship, but she had been built in secrecy so their was a great deal to be learned from the wreck, which was over 90% intact. One of the fun things that was found in her was a gold coin that confirmed a legend that her captain’s leg and possibly his life had been saved at the Battle of Shiloh, Tennessee, when a bullet struck a twenty-dollar gold piece in his pocket. The coin had been given to him by his girlfriend for luck. It was not only bent from where it had been struck, it had been engraved as follows: “Shiloh/April 6, 1862/My life Preserver/G. E. D.” [Lt. Dixon’s initials]. The Hunley has been described by government archaeologists as the most important underwater archaeological discovery of the 20th century. Although the coin was valued at over $1,000,000 and the vessel at over $20,000,000 — I chose to donate my rights to the wreck so everyone could learn from and enjoy it.

What are the difficulties you have to deal with? Especially in terms of accessibility, bureaucracy, competition, money, technical equipment and so on. The biggest problem we face is from bureaucrats who don’t want to issue a necessary permit to work and/or delay it for a host of reasons. Those reasons vary from simple ineptitude and corruption (i.e. wanting a share, job or bribe), to not understanding that shipwrecks and the artifacts from them are in constant danger from natural causes like tide and storm driven wave action, breakup, dispersal, burial, sand abrasion, as well as electrolysis, corrosion, oxidation, etc. Even marine life can cover or destroy artifacts.

Competition doesn’t bother me as much as claim jumpers who come in after you have made your discovery and try to grab credit as though they were there first. For instance, best selling novelist Clive Cussler, who often writes about shipwrecks in his novels and using them to help promote the sales of his books, has claimed to have discovered a number of shipwrecks that I had previously found and published the locations of years before he went to them. That is probably why some people believe I am the real person behind the fictional hero, Dirk Pitt, in Cussler’s books.

For most people in my business, money can be a real problem. Many projects fail due to the lack of necessary capital. But, fortunately, I have a long track record of actually discovering the wrecks that I look for, and I have a solid reputation for honoring agreements, so funding is not the real difficulty. The biggest problem is getting through the almost endless government red tape that seems to be involved with all worthwhile shipwrecks. I am going through that right now on what I believe will prove to be my most successful venture of my career.

The equipment we use is getting better all of the time, so our work in both searching and salvaging gets easier every year.

Reading about your expeditions and adventures make me think of a maritime Indiana Jones. Are you reckless when it comes to your explorations or rather careful?

I have certainly done some extremely dangerous things, but I don’t consider myself reckless and I always put the safety of my people before anything else.

You found yourself in a couple of dangerous situations. Tell us about some of the “highlights” and how you got away.

A drug lord, who had previously murdered a man in front of witnesses, once told me in no uncertain terms that I had insulted him and that he was going to kill me. My reply, especially how calmly I said it, must have made him believe I was a far bigger and more immediate threat to him than he was to me, as he turned red in his face, retracted his words and apologized to me much to the amazement of his cohorts, who had heard every word but had not understood the threat that their boss, who had looked me in the eyes, had felt.

Did you ever have a diving accident whilst looking for wrecks?

If you are asking if I have ever been seriously hurt, not really. However, I have had a great many very close calls. I have given out of air so many times I can’t remember them all. That does not normally present a real problem because most wrecks are broken open and in very shallow water. But one time I gave out of air when I was inside the wreck of the SS Regina, which was largely intact and resting upside down in almost 90 feet of water. As I was trying to find my way out I took a wrong turn and almost failed to realize it in time. Another time, I had my regulator fail while I was working inside a modern car-ferry that I was trying to raise. It took me almost four minutes without another breath to find my way out. But running out of air isn’t the only danger we face on wrecks. Once, while anchored to a section of wreckage with a steel cable, a huge wave lifted both the boat and the wreckage. As the wave subsided, it dropped the wreckage back down on top of me, pressing me into the mud bottom. I could still breathe, but I had to wait until another big wave lifted the wreckage again so I could crawl free. Still another time, I was using surface-supplied air and my air-hose got caught in the boat’s propeller. Fortunately, I had just surfaced and the boat captain saw what was happing and shut the engine down in time, thus saving my life. It was definitely a close call. I had grabbed the dive ladder and had held on for dear life. I actually bent the heavy steel pipe with which the ladder had been built, but I could not have held on any longer.

Your passion for old stuff does not stop with wrecks. You have a love for history. Why is it important for us to know about our past?

Carved on stone on the outside of the U.S. National Archives are the words “The Past is Prologue,” meaning the past tells us what is yet to come. I love research every bit as much as the diving, if not more. For me, researching the history of the ships makes the past come alive.

You are a role model and inspiration for a lot of people. Who are your role models? Who do you admire in the diving world? And in the “real “world?

Most of my role models were people I worked alongside of when I was starting out, including Robert F. Marx and Mel Fisher. Marx is best known for his many books on shipwrecks and his pioneering work in underwater archaeology. Fisher was an optimist and a dreamer, who almost went bankrupt and lost his son and daughter in law searching for the Spanish galleon Atocha but made the history books when he found it after 14 years of looking and ultimately salvaged over 40 tons of treasure. He was one of nicest men I have ever known. The biggest and most important role model in my life was my father, Col. Judson C. Spence, Sr., Ph.D., who was a true gentleman. He was honest, hard working, extremely intelligent, and truly cared about others. After he retired from the military, he got his doctorate and became the first Dean of Men at what is now Charleston Southern University. He also returned to his alma mater, the Citadel, and taught there for many years.

You co-founded a school for professional diving. What motivated you to do that and what is your teaching philosophy?

The school that I helped start is the International Diving Institute in Charleston, South Carolina. It is nationally accredited and offers instruction in surface supplied air (helmet diving); hyperbaric chamber operation; non-destruct testing; handling of hazardous materials; underwater welding; remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs); etc. Our basic course is forty hours a week for sixteen weeks, so commercial diving is not like learning scuba which can be taught in matter of hours. I must admit that I was initially motivated by the steady income I knew the school would provide me. But, because of the positive impact I observed it having on so many of our graduate’s lives, I soon came to think of the school as my most important accomplishment.

Which dangers do you see for today’s underwater world? What should young divers take into consideration and keep in mind when diving?

It is really no different than on land, the biggest dangers come from various governments trying to over regulate and seize too much control. New divers should keep in mind that the laws are constantly changing and what might be allowed today, may not be legal tomorrow, and they need to prepare for it.

Do you share the pessimistic outlook for the oceans regarding the eco systems? Are we destroying the seas and is it too late to do something about it?

Your question is really outside of my expertise, but, my answer is no. I don’t share the pessimism that many have. In many places where the commercial interests have overfished in the past the lessons have been learned. Size and catch limits have been put in place, pollution has been cutback, and fish have been brought back. Artificial reef programs have not only opened up new habits for marine life, they have taken fishing pressure off the natural reefs.

My mother is about your age and she claims that she is too old to start diving. What can you tell her?

She may too old to take up commercial diving, but, if she has no health problems that would prevent her, she could certainly take up diving for pleasure and/or, with the proper training, she could even participate in expeditions. In the past I have encouraged people who were blind or missing limbs to take up diving, so I certainly don’t see your mother’s age as a barrier. Its more about what she is interested in and about her self-confidence and attitude.

Lee, thank you from the bottom of my tank for your time.

About the Author: Bettina Winert

Schlagworte

Teilen auf

Weitere Blogbeiträge

Schreibe einene Kommentar

Deine E-Mail-Adresse wird nicht veröffentlicht.

Erforderliche Felder sind mit * markiert.

Tags

Kategorien

- Afrika (26)

- Ägypten (34)

- Albanien (5)

- An Land (46)

- Costa Rica (2)

- Deutschland (5)

- Europa (63)

- Freitauchen (6)

- Ghana (1)

- Gozo (3)

- Hotel (7)

- Individualreise (19)

- Indonesien (6)

- Italien (7)

- Jordanien (3)

- Karibik (1)

- Kroatien (14)

- Langes Wochenende (15)

- Malaysia (2)

- Malediven (5)

- Malta (2)

- Mazedonien (1)

- Mexiko (1)

- Mikronesien (2)

- Molukken (1)

- Montenegro (1)

- Mosambik (3)

- Naher Osten (3)

- Oman (1)

- Österreich (27)

- Philippinen (1)

- Reisen (73)

- São Tomé und Príncipe (1)

- Saudi Arabien (1)

- Slowakei (1)

- Slowenien (7)

- Spanien (5)

- Südafrika (1)

- Südamerika (3)

- Sudan (5)

- Südostasien (10)

- Süßwasser (10)

- Tagestrip (6)

- Tauchen (148)

- Tauchsafari (28)

- Thailand (2)

- Ungarn (4)

- Wochenendtrip (10)

- Zypern (2)